This week I continue my research on- and development of Beacon Object Files that leverage direct syscalls to perform various process injection techniques to deliver and execute shellcode.

1. What exactly is a BOF?

A Beacon Object File (BOF) is a small compiled and assembled C program. It is not linked however. When using MingW64 gcc -o bof.o -c bof.c we specify the -c flag telling MingW not to link and instead output an object file bof.o. Cobalt Strike’s Beacon agent can execute this object file in its process and use internal Beacon APIs.

BOFs are very small single-file programs that directly call WIN32 APIs. They don’t have access to a libc either, hence functions like strlen, memset and memcpy will need to be dynamically imported from Microsofts MSVCRT.dll.

2. Okay, how am I (ab)using these BOFs?

Delivering and executing shellcode on a target machine is very useful and can be done in numerous ways. Many of them use WIN32 API calls like:

- GetProcAddress

- LoadLibraryA

- OpenProcess

- VirtualAllocEx

- WriteProcessMemory

- VirtualProtect

- CreateRemoteThread

These calls are noisy and well known by EDR (Endpoint Detection and Response) and AV (Anti Virus) providers. A very popular method used by EDR/AV to detect malicious API calls, is what’s known as userland-hooking. Hooking occurs when an application intercepts an API call between two other applications.

Userland-hooking involves writing your own custom versions of the WIN32 API functions, “hooking” those API calls and replacing them with your own custom versions. When a malicous program attempts to call one of the hooked WIN32 API functions, the EDR/AV intercepts this call, inspects it, and determines whether to allow the call and continue execution, or to prevent the call or execute custom code.

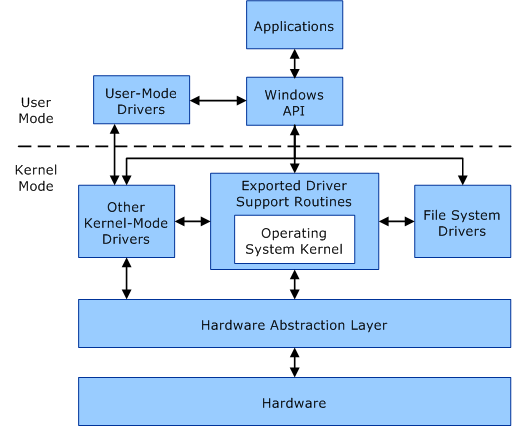

All of this happens in “user land” or User Space. To put it simple, Windows differentiates two layers: User Space and Kernel Space. Each application (like notepad.exe) creates a process when launched, and each process has a Virtual Address Space where it stores its data. User processes running in User Space have a private Virtual Address Space, system processes running in Kernel Space share a single common Virtual Address Space.

When an application needs to communicate with the Window kernel, it will first call a WIN32 API function. Most of the WIN32 API functions are contained in kernel32.dll, some more advanced functions are contained in advapi32.dll. There are a couple other libraries that house functions for graphics device interfaces and the graphical user interface, networking, common control and the Windows shell.

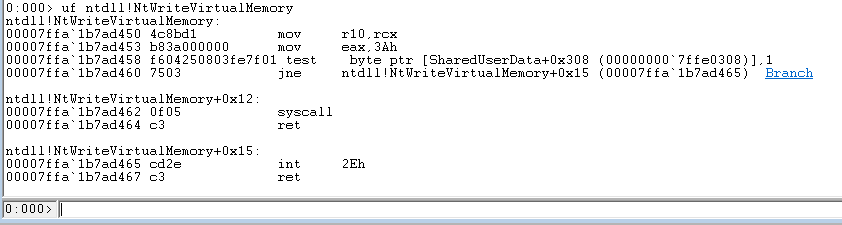

In turn, the WIN32 API functions call functions located in ntdll.dll, this library exports the Windows Native API. The Windows Native API is essentially the interface between User Space and Kernel Space. The ntdll.dll functions are implemented in ntoskrnl.exe or in other words: the Windows Kernel. These functions are commonly prefixed with Nt or Zw and are assigned a number. This number is what we call a system call or syscall for short. The function is responsible for setting up the required call arguments on the stack before moving the syscall number into the EAX register and executing the syscall instruction.

If we look at NtWriteVirtualMemory we can see the hexadecimal value 0x3A being moved into EAX at address D453. This is the syscall number. Then a couple of instructions later at address D462 we can see the syscall instruction being executed.

So, to come back to my Userland-hooking story, a common method to evade EDR/AV hooking is to skip the WIN32 API functions and directly call the underlying ntdll.dll functions. But what if EDR/AV is hooking ntdll functions as well? Well, you can’t hook what you don’t own ;) This is where direct syscalls, SysWhispers and InlineWhispers come into play.

3. So now you’re developing malware?

Essentially, yes. A lot of malware leverages the same methods, functions, techniques and tactics to do what it does. By using direct syscalls I am bypassing the WIN32 API layer as well as the ntdll.dll layer.

I’m creating my own versions of the ntdll.dll functions by copying their function prototypes and using SysWhispers to generate the required structures, datatypes, definitions and function body (assembly). InlineWhispers converts the generated function body assembly into a valid inline format to use with x64 MingW. It is important to specify the -masm=intel flag when compiling to let MingW know we’re using inline assembly according to the Intel sytax (opposed to the AT&T syntax).

The main challenge is to identify which ntdll.dll functions are called by a certain WIN32 API function. Most of the ntdll.dll functions are undocumented, which means it’s difficult to identify their function prototype, which function arguments they require and how to correctly initialize these arguments. The most effective solution I found to combat this problem is to monitor and identify API calls with API Monitor and using WinDbg to inspect the ntdll.dll functions.

4. Wrapping up

All in all I really enjoy this particular task and its challenges. It has really peaked my interest for exploit development and allowed me to see what goes on under the hood from a different perspective than analysing malware. My C/C++ skills are improving rather quickly, I’m also picking up some experience in Sleep, a scripting language for the Java platform.

Diving into the depths of the Windows Internals is a daunting but interesting adventure. Now I have yet to figure out why unsigned char shellcode[] = "super malicious shellcode goes here"; triggers a memcpy linker error…

NtDelayExecution(FALSE, 604800000);