First week of my internship and we’re starting off strong. This week I play hide and seek with C2 communications and plunge into the world of Windows Internals and Cobalt Strike.

1. printf(“Hello, world!\n”);

Hello. Thanks for reading. I would introduce myself but we both now you’re not really here for that, so let’s get right into it.

I will be researching 2 broad topics during my 8 week internship. The end goal is to create new tooling and find new techniques to help a Red Team stay undetected in a foreign environment. The topics I will cover are:

- C2 communication channels: smuggling the goodies

- Shellcode injection using Cobalt Strike’s Beacon Object Files and direct syscalls: bypassing EDR/AV

But enough with the formalities, we’ve got work to do.

2. In command, but not in control

Command & Control, also commonly referred to as C2, is the term used to denote part of an attacker’s infrastructure that is responsible for handling a large number of remote sessions.

When a target network is breached and machines compromised, the attacker needs to establish persistence, exfiltrate data, and numerous other things. On a single machine this could be achieved with just a reverse shell, but as the amount of compromised machines increases, the need for a centralized framework that can manage connections, track sessions, share sessions, create new sessions, and so on, arises.

This is where C2 framworks like Covenant, Cobalt Strike, Empire, Brute Ratel, Mythic, SharpC2 and Merlin come into play. Once a machine is compromised, an implant will be executed, usually in the form of a hidden process, which will then receive commands from the attack and send back information. The server that is responsible for sending commands to all the different implants and processing the data it gets back, is commonly called a Team Server.

It speaks for itself that a team server is a critical piece of infrastructure that contains and controls a lot of sensitive data. If the team server would be discovered by defenders and blocked, the attacker would probably loose (part of) his foothold and access to the target network. To prevent this from happening, attackers use redirectors or intermediary servers in between the target network and their own infrastructure. These redirectors could be owned by the attacker, or could be legitimate infrastructure controlled by the attacker, like CDN’s, DoH providers, etc.

A critical part of C2 infrastructure is the communication channel, method, medium, between the implant and the redirectors, as well as communication between implants themselves. It is imperative to hide the traffic from defenders and to make sure it doesn’t get blocked by internal proxy servers or firewalls.

Common protocols used by C2 frameworks to communicate over are: HTTP(s), SMB and DNS. Common methods to bypass filtering used by C2 frameworks are: Domain fronting, SaaS, DNS over HTTPS, DNS tunneling.

Domain Fronting is by far the most popular technique to hide C2 traffic, unfortunately it is coming to an end and CDN providers are cracking down on infrastructure abusing this technique, so it is time to find alternatives.

3. API stands for Attacker’s Public Infrastructure

API’s are great. They’re public infrastructure, they’re legitimate, and they’re heavily used by web applications and other legitimate software running in corporate environments which makes them near impossible to block.

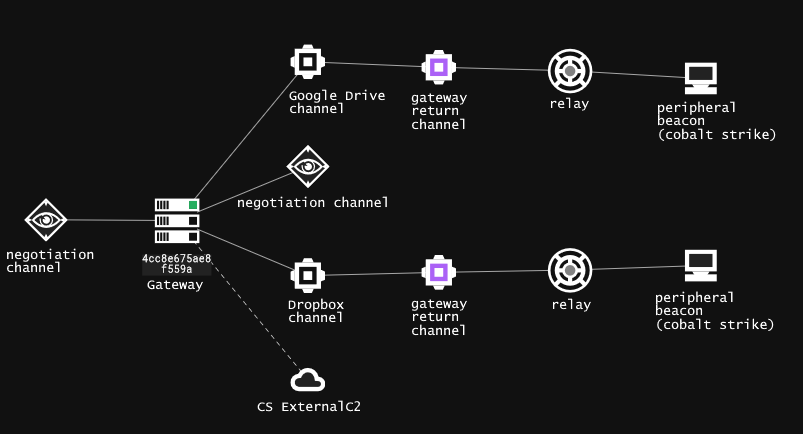

A relatively new C2 framework developed by FSecure Labs called C3 makes heavy use of public API’s from Software as a Service (SaaS) providers like Google Drive, Dropbox and Slack to create C2 channels.

C3 (Custom Command and Control) is a tool that allows Red Teams to rapidly develop and utilise esoteric command and control channels (C2). It’s a framework that extends other red team tooling, such as the commercial Cobalt Strike (CS) product via ExternalC2, which is supported at release. It allows the Red Team to concern themselves only with the C2 they want to implement; relying on the robustness of C3 and the CS tooling to take care of the rest.

- https://github.com/FSecureLABS/C3/README.md

I set up a new C3 gateway (team server) and created a channel using Google Drive and a channel using Dropbox. I integrated the C3 gateway with Cobalt Strike’s team server and delivered a Cobalt Strike Beacon over both channels to a C3 relay (implant) which will execute it in memory.

C3 is built with the idea of it being easily extendable with new channels. The framework leaves the heavy lifting to external C2 frameworks and focusses on creating reliable, isoteric channels between different components. C3 was used in the Colonial Pipeline attack by DarkSide, so I guess that goes to show its reliability and relevancy.

4. Google does everything

Even DNS over HTTPS (DoH), which is an interesting concept to look at when exfiltrating C2 traffic.

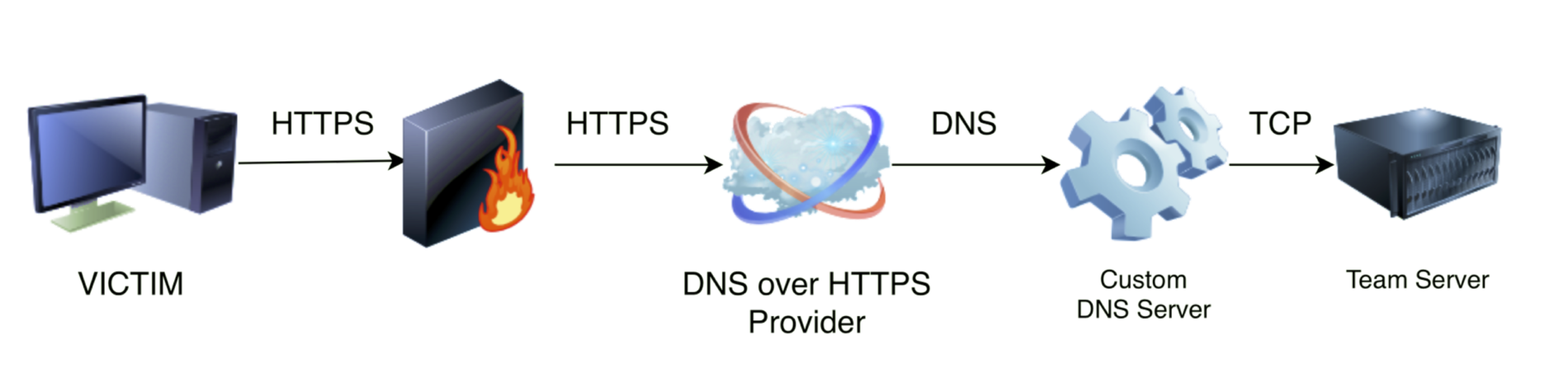

When a client visits a website using HTTPS, the classic DNS query to resolve the domain name to the IP address of the server where the website is hosted, is performed in a plaintext format. DoH attempts to change this behaviour and increase the level of privacy, by encrypting the DNS query and sending it over HTTPS to a DoH provider. The provider will then resolve the request and send back the answer over HTTPS.

There are two public Proof of Concepts (PoC) that leverage DoH to establish C2 communication. DoHC2 by SpiderLabs and godoh by SensePost.

The DoH client will split up data into chunks of 255 bytes (because the size of a DNS TXT record can maximum be 255 bytes) and append it as TXT record to the DNS request. The request is then sent to the DoH provider via HTTPS, which will forward it to the attacker controlled custom DNS server via regular DNS over port 53. The custom DNS server then reconstructs the data from the TXT records and sends back a response.

The downside of DoH based C2, is the TXT record size limit, which results in a lot of requests when sending a lot of data. If TLS stripping is in place, the DNS requests can also be observed and potentially expose the attacker’s infrastructure or data (if the data can be decrypted).

5. Wrapping up

Next week I will dive into the specifics of process injection, Beacon Object Files and Windows’s memory architecture.

NtDelayExecution(FALSE, 604800000);