This week I’m back to full HP, which means it’s time to code! On the menu are registry callbacks, doubly linked lists and a struggle with I/O in native C.

1. Interceptor 2.0

Until now, I relied on the Evil driver to patch kernel callbacks while I attempted to tackle ESET Anti-Virus, however the Evil driver only implements patching for process and thread callbacks. This week I spent a good amount of time porting over the functionality from Evil driver to Interceptor and added support for patching image load callbacks as well as a first effort at enumerating registry callbacks.

While I was working, I stumbled upon Mimidrv In Depth: Exploring Mimikatz’s Kernel Driver by Matt Hand, an excellent blogpost which aims to clarify the inner workings of Mimikatz’s kernel driver. Looking at the Mimikatz kernel driver code made me realize I’m a terrible C/C++ developer and I wish drivers were written in C# instead, but it also gave me an insight into handling different aspects of the interaction process between the kernel driver and the user mode application.

To make up for my sins, I refactored a lot of my code to use a more modular approach and keep the actual driver code clean and limited to driver specific functionality. For those interested, the architecture of Interceptor looks somewhat like this:

.

+-- Driver

| +-- Header Files

| +-- Common.h | contains structs and IOCTLs shared between the driver and CLI

| +-- Globals.h | contains global variables used in all modules

| +-- pch.h | precompiled header

| +-- Interceptor.h | function prototypes

| +-- Intercept.h | function prototypes

| +-- Callbacks.h | function prototypes

+-- Source Files

| +-- pch.cpp

| +-- Interceptor.cpp | driver code

| +-- Intercept.cpp | IRP hooking module

| +-- Callbacks.cpp | Callback patching module

+-- CLI

| +-- Source Files

| +-- InterceptorCLI.cpp

2. Driver I/O and why it’s a mess

Something else that needs overhauling is the way the driver handles I/O from the user mode application. When the user mode application requests a listing of all the present drivers on the system, or the registered callbacks, a lot of data needs to be collected and send back in an efficient and structured manner. I’m not particularly fussy about speed or memory usage, but I would like to keep the code tidy, easy to read and understand and keep the risk of dangling pointers and memory leaks at a minimum.

Drivers typically handle I/O via 3 different ways:

- Using the IRP_MJ_READ dispatch routine with

ReadFile() - Using the IRP_MJ_WRITE dispatch routine with

WriteFile() - Using the IRP_MJ_DEVICE_CONTROL dispatch routine with

DeviceIoControl()

Using 3 different methods:

- Buffered I/O

- Direct I/O

- On a IOCTL basis

- METHOD_NEITHER

- METHOD_BUFFERED

- METHOD_IN_DIRECT

- METHOD_OUT_DIRECT

Since Interceptor returns different data depending on the request (IRP) it received, the I/O is handled in the IRP_MJ_DEVICE_CONTROL dispatch routine on a IOCTL basis using METHOD_BUFFERED. As discussed in Week 2, an IRP is accompanied by one or more IO_STACK_LOCATION structures which we can retrieve using IoGetCurrentIrpStackLocation(). The current stack location is important, because it contains several fields with information regarding user buffers.

When using METHOD_BUFFERED, the I/O Manager will assist us with managing resources. When the request comes in, the I/O manager will allocate the system buffer from non-paged pool memory (non-paged pool memory is always present in RAM) with a size that is the maximum of the lengths of the input and output buffers and then copy the user input buffer to the system buffer. When the request is complete, the I/O manager copies the specified number of bytes from the system buffer to the user output buffer.

PIO_STACK_LOCATION stack = IoGetCurrentIrpStackLocation(Irp);

//size of user input buffer

size_t szBufferIn = stack->Parameters.DeviceIoControl.InputBufferLength;

//size of user output buffer

size_t szBufferOut = stack->Parameters.DeviceIoControl.OutputBufferLength;

//system buffer used for both reading and writing

PVOID bufferInOut = Irp->AssociatedIrp.SystemBuffer;

Using buffered I/O has a drawback, namely we need to define common I/O structures for use in both driver and user mode application, so we know what input, output and size to expect. As an example we will pass an index and driver name from our user mode application to our driver:

//Common.h

struct USER_DRIVER_DATA {

char driverName[256];

int index;

}

//ApplicationCLI.cpp

DWORD lpBytesReturned;

USER_DRIVER_DATA inputBuffer;

data.index = 1;

data.driverName = "\\Driver\\MyDriver";

DeviceIoControl(hDevice, IOCTL_MYDRIVER_GET_DRIVER_INFO, &inputBuffer, sizeof(inputBuffer), nullptr, 0, &lpBytesReturned, nullptr);

//MyDriver.cpp

auto data = (USER_DRIVER_DATA*)Irp->AssociatedIrp.SystemBuffer;

int index = data->index;

char driverName[256];

strcpy_s(driverName, data->driverName);

Using this approach, we quickly end up with a lot of different structures in Common.h for each of the different I/O requests, so I went looking for a “better”, more generic way of handling I/O. I decided to look at the Mimikatz kernel driver code again for inspiration. The Mimikatz driver uses METHOD_NEITHER, combined with a custom buffer and a wrapper around the RtlStringCbPrintfExW() function.

When using METHOD_NEITHER, the I/O Manager is not involved and it is up to the driver itself to manage the user buffers. The input and output buffer are no longer copied to and from the system buffer.

PIO_STACK_LOCATION stack = IoGetCurrentIrpStackLocation(Irp);

//using input buffer

PVOID bufferIn = stack->Parameters.DeviceIoControl.Type3InputBuffer;

//user output buffer

PVOID bufferOut = Irp->UserBuffer;

The idea behind the Mimikatz approach is to declare a single buffer structure and a wrapper kprintf() around RtlStringCbPrintfExW():

typedef struct _MY_BUFFER {

size_t* szBuffer;

PWSTR* Buffer;

} MY_BUFFER, * PMY_BUFFER;

#define kprintf(MyBuffer, Format, ...) (RtlStringCbPrintfExW(*(MyBuffer)->Buffer, *(MyBuffer)->szBuffer, (MyBuffer)->Buffer, (MyBuffer)->szBuffer, STRSAFE_NO_TRUNCATION, Format, __VA_ARGS__))

The kprintf() wrapper accepts a pointer to our buffer structure MY_BUFFER, a format string and multiple arguments to be used with the format string. Using the provided format string, it will write a byte-counted, null-terminated text string to the supplied buffer *(MyBuffer)->Buffer.

Using this approach, we can dynamically allocate our user output buffer using bufferOut = LocalAlloc(LPTR, szBufferOut), this will allocate the specified number of bytes (szBufferOut) as fixed memory memory on the heap and initialize it to zero (LPTR (0x0040) flag = LMEM_FIXED (0x0000) + LMEM_ZEROINIT (0x0040) flags).

We can then write to this output buffer in our driver using the kprintf() wrapper:

MY_BUFFER kOutputBuffer = { &szBufferOut, (PWSTR*)&bufferOut };

szBufferOut = stack->Parameters.DeviceIoControl.OutputBufferLength;

bufferOut = Irp->UserBuffer;

szBufferIn = stack->Parameters.DeviceIoControl.InputBufferLength;

bufferIn = stack->Parameters.DeviceIoControl.Type3InputBuffer;

kprintf(&kOutputBuffer, L"Input: %s\nOutput: %s\n", bufferIn, L"our output");

ULONG_PTR information = stack->Parameters.DeviceIoControl.OutputBufferLength - szBufferOut;

return CompleteIrp(Irp, status, information);

If the output buffer appears too small for all the data we wish to write, kprintf() will return STATUS_BUFFER_OVERFLOW. Because the STRSAFE_NO_TRUNCATION flag is set in RtlStringCbPrintfExW(), the contents of the output buffer will not be modified, so we can increase the size, reallocate the output buffer on the heap and try again.

3. Recalling the callbacks

As mentioned in previous blogposts, locating the different callback arrays and implementing a function to patch them was fairly straight forward. Apart from process and thread callbacks, I also added in the PsLoadImageNotifyRoutineEx() callback, which alerts a driver whenever a new image is loaded or mapped into memory.

Registry and Object creation/duplication callbacks work slightly different when it comes to how the callback function addresses are stored. Instead of a callback array containing function pointers, the function pointers for registry and object callbacks are stored in a doubly linked list. This means that instead of looking for a callback array address, we’ll be looking for the address of the CallbackListHead.

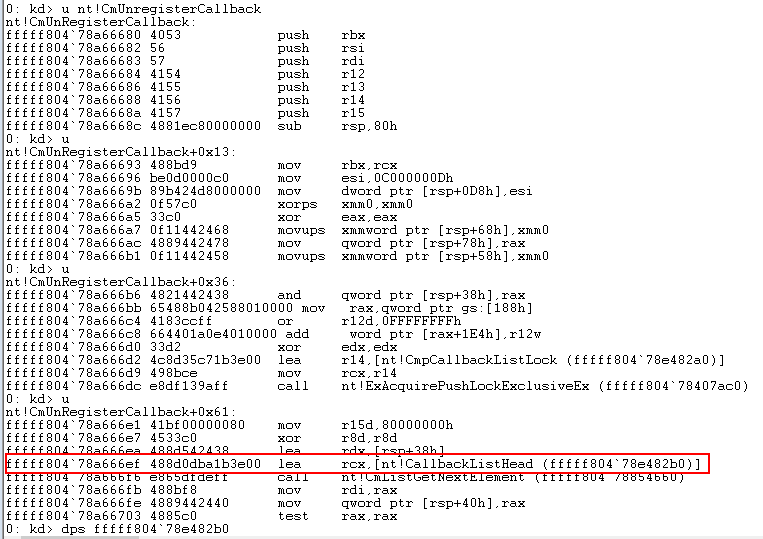

Instead of going the same route as with obtaining the address for the callback arrays by enumerating the instructions in the NotifyRoutine() functions looking for a series of opcodes, I decided to instead enumerate the CmUnRegisterCallback() function, which is used to remove a registry callback. The reason behind this approach is that in order to obtain the CallbackListHead address via CmRegisterCallback(), we need to follow 2 jumps (0xE8) to CmpRegisterCallbackInternal() and CmpInsertCallbackInListByAltitude(). Instead, by using CmUnRegisterCallback(), we only need to look for a LEA, RCX (0x48 0x8d 0x0d) instruction which puts the address of the CallbackListHead into RCX.

ULONG64 FindCmUnregisterCallbackCallbackListHead() {

UNICODE_STRING func;

RtlInitUnicodeString(&func, L"CmUnRegisterCallback");

ULONG64 funcAddr = (ULONG64)MmGetSystemRoutineAddress(&func);

ULONG64 OffsetAddr = 0;

for (ULONG64 instructionAddr = funcAddr; instructionAddr < funcAddr + 0xff; instructionAddr++) {

if (*(PUCHAR)instructionAddr == OPCODE_LEA_RCX_7[g_WindowsIndex] &&

*(PUCHAR)(instructionAddr + 1) == OPCODE_LEA_RCX_8[g_WindowsIndex] &&

*(PUCHAR)(instructionAddr + 2) == OPCODE_LEA_RCX_9[g_WindowsIndex]) {

OffsetAddr = 0;

memcpy(&OffsetAddr, (PUCHAR)(instructionAddr + 3), 4);

return OffsetAddr + 7 + instructionAddr;

}

}

return 0;

}

Once we have the CallbackListHead address, we can use it to enumerate the doubly linked list and retrieve the callback function pointers. The structure we’re working with can be defined as:

typedef struct _CMREG_CALLBACK {

LIST_ENTRY List;

ULONG Unknown1;

ULONG Unknown2;

LARGE_INTEGER Cookie;

PVOID Unknown3;

PEX_CALLBACK_FUNCTION Function;

} CMREG_CALLBACK, *PCMREG_CALLBACK;

The registered callback function pointer is located at offset 0x28.

PVOID* CallbackListHead = (PVOID*)FindCmUnregisterCallbackCallbackListHead();

PLIST_ENTRY pEntry;

ULONG64 i;

if (CallbackListHead) {

for (pEntry = (PLIST_ENTRY)*CallbackListHead, i = 0; NT_SUCCESS(status) && (pEntry != (PLIST_ENTRY)CallbackListHead); pEntry = (PLIST_ENTRY)(pEntry->Flink), i++) {

ULONG64 callbackFuncAddr = *(ULONG64*)((ULONG_PTR)pEntry + 0x028);

KdPrint((DRIVER_PREFIX "[%02llu] 0x%llx\n", i, callbackFuncAddr));

//<truncated>

}

}

4. Conclusion

In this blogpost we took a brief look at the structure of the Interceptor kernel driver and how we can handle I/O between the kernel driver and user mode application without the need to create a crazy amount of structures. We then ventured back into callback land and took a peek at obtaining the CallbackListHead address of the doubly linked list containing registered registry callback function pointers (try saying that quickly 5 times in a row ;) ).